From Wikipedia

In the oldest texts of Buddhism, dhyāna (Sanskrit) or jhāna (Pāḷi) is the training of the mind, commonly translated as meditation, to withdraw the mind from the automatic responses to sense-impressions, and leading to a “state of perfect equanimity and awareness (upekkhā-sati-parisuddhi).” Dhyāna may have been the core practice of pre-sectarian Buddhism, in combination with several related practices which together lead to perfected mindfulness and detachment and are fully realized with the practice of dhyana.

In the later commentarial tradition, which has survived in present-day Theravāda, dhyāna is equated with “concentration,” a state of one-pointed absorption in which there is a diminished awareness of the surroundings. In the contemporary Theravāda-based Vipassana movement, this absorbed state of mind is regarded as unnecessary and even non-beneficial for awakening, which has to be reached by mindfulness of the body and vipassanā (insight into impermanence). Since the 1980s, scholars and practitioners have started to question this equation, arguing for a more comprehensive and integrated understanding and approach, based on the oldest descriptions of dhyāna in the suttas.

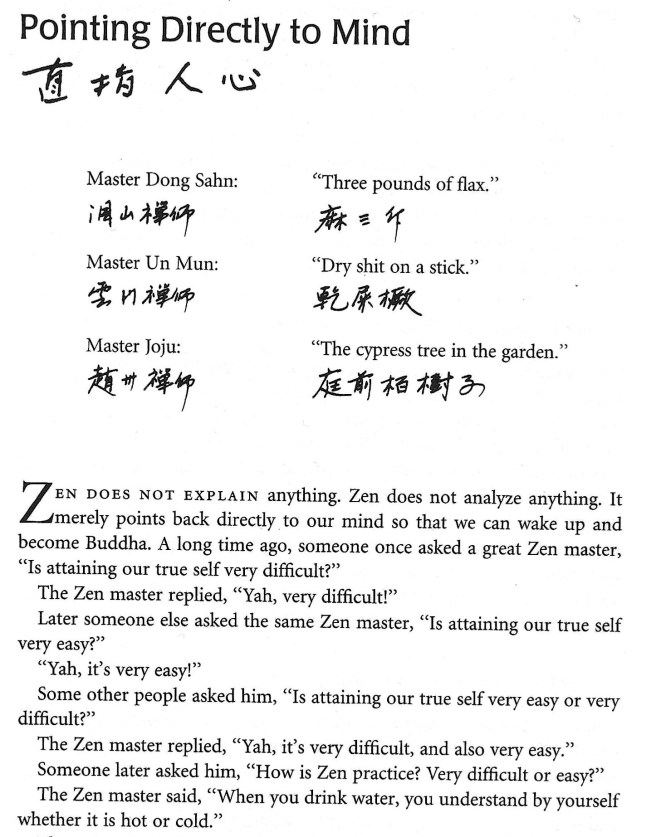

In Chán and Zen, the names of which Buddhist traditions are the Chinese and Japanese pronunciations, respectively, of dhyāna, dhyāna is the central practice, which is ultimately based on Sarvastivāda meditation practices, and has been transmitted since the beginning of the Common Era.

Etymology

Dhyāna, from Proto-Indo-European root *√dheie-, “to see, to look,” “to show.” Developed into Sanskrit root √dhī and n. dhī, which in the earliest layer of text of the Vedas refers to “imaginative vision” and associated with goddess Saraswati with powers of knowledge, wisdom and poetic eloquence. This term developed into the variant √dhyā, “to contemplate, meditate, think”, from which dhyāna is derived.

According to Buddhaghosa (5th century CE Theravāda exegete), the term jhāna (Skt. dhyāna) is derived from the verb jhayati, “to think or meditate,” while the verb jhapeti, “to burn up,” explicates its function, namely burning up opposing states, burning up or destroying “the mental defilements preventing […] the development of serenity and insight.”

Commonly translated as meditation, and often equated with “concentration,” though meditation may refer to a wider scala of exercises for bhāvanā, development. Dhyāna can also mean “attention, thought, reflection.”

The jhānas

The Pāḷi canon describes four progressive states of jhāna called rūpa jhāna (“form jhāna“), and four additional meditative states called arūpa (“without form”).

Preceding practices

Meditation and contemplation are preceded by several practices, which are fully realized with the practice of dhyāna. As described in the Noble Eightfold Path, right view leads to leaving the household life and becoming a wandering monk. Sīla (morality) comprises the rules for right conduct. Right effort, or the four right efforts, aim to prevent the arising of unwholesome states, and to generate wholesome states. This includes indriya samvara (sense restraint), controlling the response to sensual perceptions, not giving in to lust and aversion but simply noticing the objects of perception as they appear. Right effort and mindfulness calm the mind-body complex, releasing unwholesome states and habitual patterns, and encouraging the development of wholesome states and non-automatic responses. By following these cumulative steps and practices, the mind becomes set, almost naturally, for the practice of dhyāna. The practice of dhyāna reinforces the development of wholesome states, leading to upekkhā (equanimity) and mindfulness.

The rūpa jhānas

Qualities of the rūpa jhānas

The practice of dhyāna is aided by ānāpānasati, mindfulness of breathing. The Suttapiṭaka and the Agamas describe four stages of rūpa jhāna. Rūpa refers to the material realm, in a neutral stance, as different from the kāma realm (lust, desire) and the arūpa-realm (non-material realm). Each jhāna is characterised by a set of qualities which are present in that jhāna.

- First dhyāna: the first dhyāna can be entered when one is secluded from sensuality and unskillful qualities, due to withdrawal and right effort. There is pīti (“rapture”) and non-sensual sukha (“pleasure”) as the result of seclusion, while vitarka-vicara (“discursive thought”) continues.

- Second dhyāna: there is pīti (“rapture”) and non-sensual sukha (“pleasure”) as the result of concentration (samadhi-ji, “born of samadhi”); ekaggata (unification of awareness) free from vitarka-vicara (“discursive thought”); sampasadana (“inner tranquility”).

- Third dhyāna: upekkhā (equanimous; “affective detachment”), mindful, and alert, and senses pleasure with the body.

- Fourth dhyāna: upekkhāsatipārisuddhi (purity of equanimity and mindfulness); neither-pleasure-nor-pain. Traditionally, the fourth jhāna is seen as the beginning of attaining psychic powers (abhijñā).

The arūpas

Grouped into the jhāna-scheme are four meditative states referred to in the early texts as arūpas. These are also referred to in commentarial literature as immaterial/formless jhānas (arūpajhānas), also translated as The Formless Dimensions, to be distinguished from the first four jhānas (rūpa jhānas). In the Buddhist canonical texts, the word “jhāna” is never explicitly used to denote them; they are instead referred to as āyatana. However, they are sometimes mentioned in sequence after the first four jhānas (other texts, e.g. MN 121, treat them as a distinct set of attainments) and thus came to be treated by later exegetes as jhānas. The immaterial are related to, or derived from, yogic meditation, while the jhānas proper are related to the cultivation of the mind. The state of complete dwelling in emptiness is reached when the eighth jhāna is transcended.

The four arūpas are:

- fifth jhāna: infinite space (Pāḷi ākāsānañcāyatana, Skt. ākāśānantyāyatana),

- sixth jhāna: infinite consciousness (Pāḷi viññāṇañcāyatana, Skt. vijñānānantyāyatana),

- seventh jhāna: infinite nothingness (Pāḷi ākiñcaññāyatana, Skt. ākiṃcanyāyatana),

- eighth jhāna: neither perception nor non-perception (Pāḷi nevasaññānāsaññāyatana, Skt. naivasaṃjñānāsaṃjñāyatana).

Although the “Dimension of Nothingness” and the “Dimension of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception” are included in the list of nine jhānas taught by the Buddha they are not included in the Noble Eightfold Path. Noble Truth number eight is sammā samādhi (Right Concentration), and only the first four jhānas are considered “Right Concentration.” If he takes a disciple through all the jhānas, the emphasis is on the “Cessation of Feelings and Perceptions” rather than stopping short at the “Dimension of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception”.

Nirodha-samāpatti

Beyond the dimension of neither perception nor non-perception lies a state called nirodha samāpatti, the “cessation of perception, feelings and consciousness”. Only in commentarial and scholarly literature, this is sometimes called the “ninth jhāna“

—————————————————————————————————

And from Wikipédia

Dhyāna

Dhyāna (sanskrit : ध्यान (devanāgarī) ; pali : झान, romanisation, jhāna ; chinois simplifié : 禅 ; chinois traditionnel : 禪 ; pinyin : chán ; coréen : 선, translit. : seon ; zen (禅) ; vietnamien : thiền ; tibétain : བསམ་གཏན, Wylie : bsam gtan, THL : Samten) est un terme sanskrit qui correspond dans les Yoga Sūtra de Patañjali au septième membre (aṅga) du Yoga. Ce terme désigne des états de concentration cultivés dans l’hindouisme, le bouddhisme, et le jaïnisme. Il est souvent traduit par « absorption », bien qu’étymologiquement il signifie simplement méditation ou contemplation. Le terme méditation est utilisé aujourd’hui comme un mot désignant de nombreuses techniques en occident, il s’apparente à la vigilance en psychologie ou en philosophie. Historiquement et pour le sous-continent indien, dhyana en est le plus proche.

Patañjali, le compilateur des Yoga Sūtra, en fait une étape préliminaire du samādhi. Les deux termes sont interchangés pour désigner ces états de conscience « transcendants ». Par exemple, les traductions Ch’an en chinois, Sŏn en coréeen, Thiền en vietnamien et Zen en japonais sont des noms d’écoles de dhyāna bouddhistes, dérivées les unes des autres, où dhyāna prend ce sens fort de samādhi.

On rencontre plus souvent, en bouddhisme, le terme pāli jhāna, parce que les enseignements qui y sont liés sont plutôt une préoccupation de l’école Theravāda.

Therāvada

Atteindre les jhānas correspond au développement de la tranquillité et de la sagesse (voir Samatha bhavana). On distingue cinq jhānas de la forme ou de la sphère physique pure, et quatre jhanas dans la méditation sur les royaumes immatériels. Anapanasati est la principale technique d’accès aux jhānas, la méditation metta en est une autre. Ces jhānas sont différenciés en fonction des « facteurs » qui les caractérisent :

- Application initiale (mouvement de l’esprit vers l’objet de méditation) : vitakka ;

- Application soutenue (saisie de l’objet par l’esprit) : vicāra ;

- Joie, ravissement : piti ;

- Bonheur : sukha ;

- Concentration en un point : ekaggata ;

- Équanimité : upekkha.

Pour être atteints, les jhānas nécessitent la suppression de cinq empêchements :

- le désir des sens (kāmacchanda) ;

- la colère ou l’animosité (vyāpāda) ;

- la paresse ou la torpeur (thīna-middha) ;

- l’agitation ou le remords (uddhacca-kukkucca) ;

- le doute (vicikicchā).

Les cinq jhānas du monde de la forme comportent tous des facteurs différents ; leur nombre est souvent réduit à quatre (en ne tenant pas compte d’un état intermédiaire entre le premier et le deuxième, dépourvu de vitakka, mais avec un reste de vicāra) :

- premier dhyâna : vitakka, vicāra, piti, sukha et ekaggata (le monde des cinq sens est complètement transcendé) ;

- deuxième dhyâna : piti, sukha et ekaggata (il n’y a plus d’action, de mouvement du mental, sont seulement ressentis la joie et le bonheur).

- troisième dhyâna : sukha et ekaggata (seul le bonheur demeure).

- quatrième dhyâna : upekkha et ekaggata (pure équanimité, il y a arrêt temporaire de la respiration dans cet état).

Ces deux facteurs, équanimité et concentration, resteront présents dans les 4 jhānas du sans-forme ou non physiques.

Les quatre royaumes immatériels de la méditation sont :

- la sphère de l’espace infini

- la sphère de la conscience infinie

- la sphère du néant

- la sphère sans perception et sans non-perception